anchorOne Project, many Goals

Our goals for the new website were manifold:

- We wanted to update the rather antiquated design of the old site and create a modern design language that represented our identity well and was build on a design system that we could build on in the future (the details of which are to be covered in a separate, future post).

- We wanted to keep creating and maintaining content for the site as simple as it was with the previous site that was built on Jekyll and published via GitHub Pages; for example adding new blog posts should remain as easy as adding a new Markdown file with some front matter.

- Although we are huge fans of Elixir and Phoenix we did not want to create an API server for the site that would serve content etc. as that would have added quite some unnecessary complexity and should generally not be necessary for a static site like ours anyway where all content is known upfront and nothing ever needs to be calculated dynamically on the server.

- We wanted to have best in class performance so that the site would load as fast as possible even in slow network situations and even without JavaScript as well as offline of course.

anchorStatic Prerendering + Rehydration and CSR

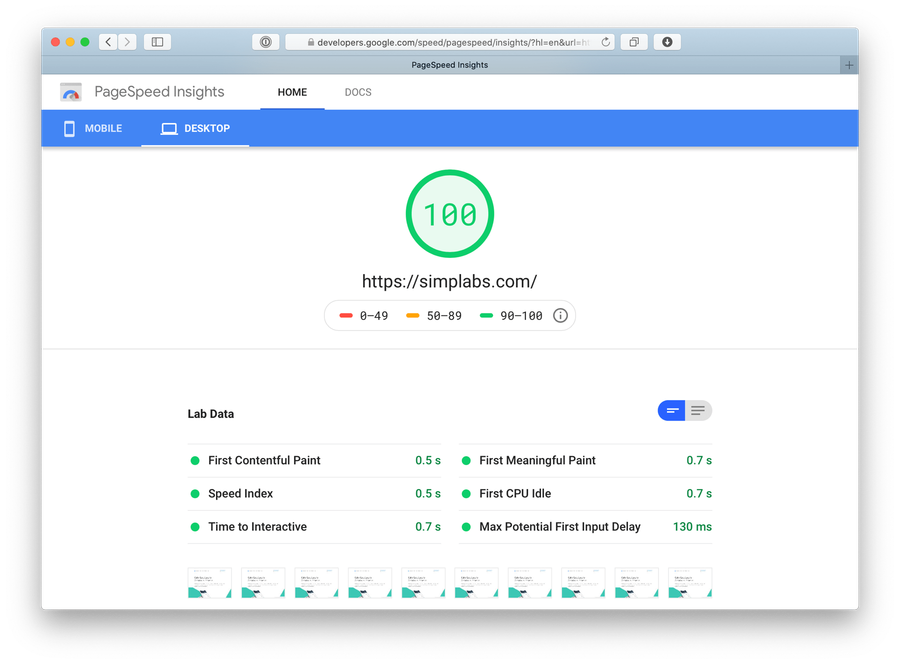

Since the site is entirely static content, it was clear we wanted to serve pre-rendered HTML files for all pages – there was no point delaying the first paint until some JavaScript bundle was loaded. Those static HTML documents would be served via a CDN for an optimal Time to First Byte (TTFB). As the pages were pre-rendered and did not depend on any client-side JavaScript, that would also result in a fast First Contentful Paint (FCP). Since there is no interactivity on any of the pages really, once the pages are rendered by the browser, they are also immediately interactive, meaning that Time to Interactive (TTI) is essentially the same as FCP in our case.

However, one of the advantages of client-side rendering is that all subsequent page transitions after the initial render can be handled purely on the client side without the need to make (and wait for the response to) any additional requests. In order to combine that benefit with those of serving pre-rendered HTML documents, we wrote the site as a single-page app so that the client-side app would rehydrate on top of the pre-rendered DOM once the JavaScript was loaded and the app started. If that happens before a user clicks any of the links on any of the pages, the page transition would be handled purely on the client side and thus be instant. If a link is clicked before the app is running in the client, that click would simply result in a regular navigation request that would be responded to with another pre-rendered HTML document from the CDN. In that sense, the client-side app progressively enhances the static HTML document - if it is running, page transitions will be purely client-side and instant, if it is not (yet) running, clicks on links will simply be regular navigation requests.

anchorGlimmer.js

Since we are huge fans of Ember.js and are heavily connected with the community, supporting it and even directly involved in its core team, we wanted to stay in the ecosystem to build our own site as well. While Ember.js is a great fit for ambitious apps like travel booking systems or appointment scheduling systems that implement significant client side logic though, for a static page like ours it would admittedly not have been an ideal fit – we would simply not have needed or used much of what it comes with. Ember.js' lightweight sister project Glimmer.js provides exactly what we need though, which is a system for defining and rendering components and trees of components that would get re-rendered upon changes to the application state.

The only client-side state that our application maintains is the currently active route that maps to a particular component that renders the page for that route. Leveraging Navigo for the routing and combining that with Glimmer.js for the rendering we started out with a custom micro-framework with a size of only around 30KB of JavaScript. Given that we didn't even require the JS to be loaded in order for the page to be rendered or ready to use at all, that seemed pretty good. Our main JavaScript bundle that contains Glimmer.js, Navigo and all of the main site's content only weighs in at around 70KB (as of the writing of this post) and once that is loaded all of the main site is running in the browser, meaning no additional network requests are necessary when browsing the site.

anchorStatically Prerendering

Statically pre-rendering a client-side app at build time is relatively straight forward. As part of our Netlify deployment, we build the app and start a small Express Server that serves it. We then visit each of the routes with a headless instance of Chrome using Puppeteer, take a snapshot of the page's DOM and save that to a respectively named file. All of these HTML files, along with the app itself and all other assets, then get uploaded to the CDN to be served from there.

anchorMaintaining content

Although we were switching to a significantly more advanced setup than what we had with the previous Jekyll-based site, we did not want to give up the easy maintenance of content, specifically for blog posts and similar content that we wanted to keep in Markdown files as we used to. Writing a new post should remain as easy as adding a new markdown file with some front matter and Markdown-formatted content. At the same time, we did not want to rely on an API for loading the content of particular pages dynamically as that would have added significant additional complexity and none of our data actually needed to be computed on demand on the server as all of it is indeed static and known upfront. Leveraging Glimmer.js' Broccoli-based build pipeline, we set up a process that reads in all files in a directory and converts the Markdown files into Glimmer.js components at build time.

That way we are generating dedicated components for all posts that are all mapped to their own routes. We also generate the components for the blog listing page(s) and the ones that list all posts by a particular author. This approach basically moves what would typically be done by an API server at runtime (retrieving content from a repository that grows and changes over time) to build time, much like what the Jamstack advocates for (and tools like Empress, VuePress or Gatsby would have done out of the box 😀). The same approach is used for other parts of the website that grow and change over time and that we want to be able to maintain content for with little effort like the calendar or talks catalog.

anchorBundling and Caching

When all of a site's content is encoded in components that are written in JavaScript, that means that JavaScript bundle will significantly grow over time. In order to avoid that all of our users had to load all of the site's content on each visit, we wanted to split the JavaScript into separate bundles so that everyone only needs to load what is (likely to be) relevant for them. Anything that was not loaded already would be loaded lazily once the user navigated to the respective part of the site (and ideally be served from the service worker cache - more on that below). One approach for achieving such a split is to split individual bundles for all of the pages in a site but that means that any page transitions will result in an additional request to load the bundle that contains the content for the particular target page. We knew we did not want that but handle as many page transitions purely on the client side without the need for additional network requests as we could.

The approach that we went with was to define bundle boundaries on usage patterns and split along those so that only few network requests would be necessary to load the JavaScript bundles that were actually relevant for a particular user. Our site now has a multitude of bundles:

- the main bundle that contains Glimmer.js itself as well as all of the main site's content; that is about 70KB as of the writing of this post

- the bundles for each of the blog's listing pages as well as individual bundles for each post; these are relatively small but change frequently of course

- bundles for rarely accessed pages like imprint and privacy policy that have a significant size (around 11KB as of the writing of this post) but contain content that is accessed only by very few users

- additional bundles for more frequently changing content like the calendar or talks catalog

- a bundle that contains a component that lists the most recent blog posts for a particular topic that; that component gets included on pages within the main site

anchorBundles and Caching

Another factor to take into account when defining bundle boundaries is the stability of each bundle in the sense of how often it is going to change over time. Our main bundle that contains Glimmer.js and the site's main content is relatively stable and will typically not change for longer periods of time (potentially weeks or months). That means once it is cached in a user's browser, there is a good chance they will be able to reuse it from cache upon their next visit. If we had included all of the components for all of the blog posts in that main bundle though, we would not only have steadily grown that bundle over time but also invalidated the users's cache for it every time we released a new post. The same is true for the component that renders a list of recent posts for a particular topic. As that component is always needed along with components that are part of the main bundle as it is rendered on the respective pages, we could have included it right with the main bundle, but that would likewise have meant invalidating the main bundle with every blog post which would have resulted in a poor utilisation of our user's caches.

anchorCaching Strategies

As described, we optimized our bundles for cache-ability. Since we also use fingerprinted asset names (or actually get them for free out of the box since Glimmer.js uses Ember CLI), we can let our user's browsers cache all resources indefinitely using immutable caching:

cache-control: public,max-age=31536000,immutable

The immutable caching directive tells the browser that the respective resource can never change and may be cached indefinitely. The max-age directive is only necessary as a fallback for browsers that do not support immutable caching. An immutable resource that the browser has cached will be available instantly on the next visit to the respective page and should generally have the same performance characteristics as a resource cached in a service worker's cache.

anchorService Worker

Of course we also install a service worker that caches all of the page's resources to further improve caching and make the page work offline. The service worker loads of the JavaScript bundles described above into its cache eagerly. So even some of the pages' content is split into separate bundles that are loaded lazily, when that lazy load is triggered the respective bundle is likely to be in the service worker's cache already and be served from there so that the page transition can still be instant without a network request.

anchorStatic Prerendering and service workers

When using service workers on a site with statically pre-rendered HTML, there is one caveat to be aware of when it comes to serving HTML from the service worker when the device is offline. Since every route on the page has its own HTML page that contains precisely the content for that page, not all HTML requests can be served with the same response from the service worker. Since the JavaScript bundle will be served from the service worker as well when the page starts offline, serving a pre-rendered HTML document is not necessary anyway though as there is no significant delay for loading the JavaScript. Instead, we can simply serve an empty HTML document in this scenario. That document only contains a

<div id="app"></div>in its <body> that the application will render into once it starts up.

anchorMore

All of the above has lead to a result we are pretty happy with. While the design of our new page is for everyone to judge based on their own taste maybe, the performance numbers speak a clear language.

We were able to get there without giving up on the ease of maintenance of the content so that writing a new blog post is as easy as adding a Markdown file and opening a pull request.

And even though we spent an unreasonable amount of time and effort during the course of the project, there are many more things that we did not do or that I couldn't cover in this article but that should be considered best practices when optimizing for performance:

- CSS and optimizing it has huge potential to have significant positive impact on a site's performance (and sink lots of time 🎉); we used CSS Blocks which is great but worth a blog post of its own so I won't go into any details here.

- Images and their formats are a huge topic as well when it comes to performance and there are many low hanging fruits where simple changes can have a significant positive impact on a site's performance; things like inlining SVGs (or not if they are big or change often), using progressive JPGs or base64-encoded background images that get swapped out with the actual image after page load are to be named as well as using progressive images to avoid huge payloads on small viewports.

- Third-parties can have a significant negative impact on a site's performance and should generally be avoided (for example, you'll want to serve fonts from your own domain).

- Optimizing for performance is an ongoing project and not a one-off effort; there needs to be tooling in place to be aware of degrations and accidental mistakes, e.g. you could have Lighthouse integrated into your Github Pipeline (ideally for every route of the app), jobs that tell you how much weight a change adds to which bundles and which bundles it invalidates etc.

- Knowing is better than guessing and if you really care about your site's performance you need to measure using RUM.

By spending a significant (and maybe unreasonable) amount of time and energy we ended up with the highly optimized site you're looking at. The downside is we ended up with our own custom static site generator essentially that we now need to maintain ourselves (one of the reasons why we recommend using a fully integrated framework like Ember.js instead of compiling your own custom framework out of a bunch of micro libraries). However, it was definitely an interesting experiment and we hope you take some inspiration out of the patterns and mechanisms we describe in this post. If you are struggling with performance in your Ember.js or Glimmer.js or other apps, feel free to reach out and talk to our experts to see how we can help.